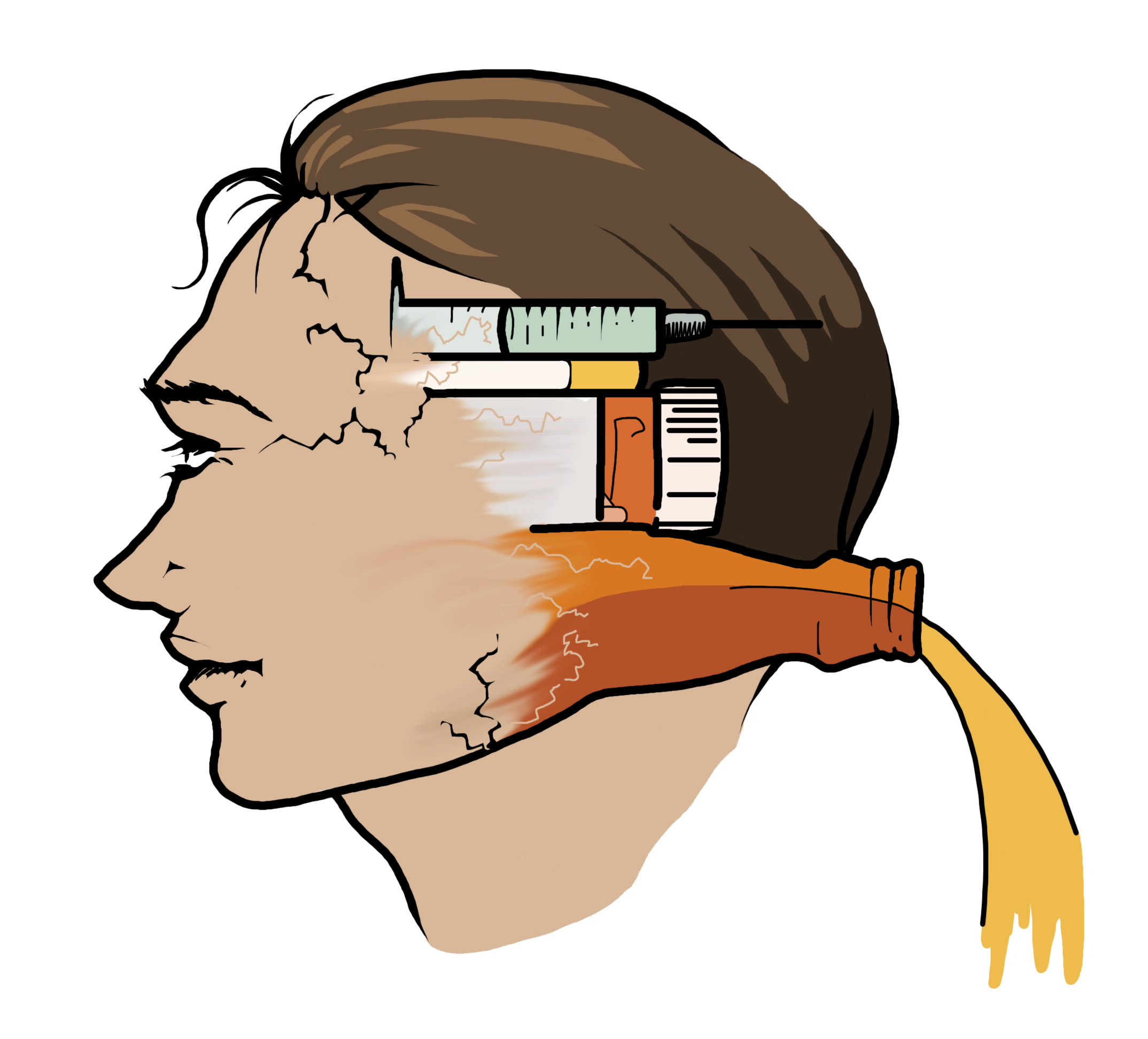

When we think of the word addiction, our thoughts go to all sorts of different places. Some people think of loved one’s that struggle with substance abuse, others think of alcoholism or gambling problems and others attribute the word to less traditional things, like too much time spent on Facebook or shopping. While it is such a prevalent word in our society, it also fair to say that it is really not that well understood. Questions like ‘is addiction just a negative thing’, ‘what types of people are more likely to become addicted to something’ and just ‘what happens to the mind and brain when you develop an addiction’ are things we all think we know a little bit about, but do not really understand fully.

Kirk Elliott, a therapist at Vanier Children’s Services in London, Ontario, is the first to point out how much there is that we still do not know, and how complicated it is. But in the fields of neuroscience psychology and scientific research, breakthroughs are being made every day, and a lot of information on the subject is available that we may not be aware of.

“The truth is, there are certain areas that are being activated in the brain in all sorts of addiction, like pathological gambling, illicit drug use, eating disorders and whatever else,” Elliott says. He described mental health as a continuum, and said compulsive shopping would be at one end, and stuff like heavy drug abuse would be on the opposite end. “Everybody is susceptible to addiction of some kind.”

In terms of how people become addicted and what influences them, Eliott says there are two big factors. The first is genetics. While it is common knowledge that your genes can influence your likelihood of certain addictions or disorders, there is really no found set of genes that explain addiction, but studies have shown that there is indeed a heritable component. This is the study of epigenetics. “Our environment can explain our gene expression— which genes are blocked, and which are activated. So psychologists are thinking, if an individual uses drugs or addictive behaviour, that can change their genes, and pass it to their offspring,” explains Elliott, adding that the research is in motion, and new revelations are discovered regularly.

The other factor is what promotes and drives people to addictive behaviour. It can be to self-medicate, or the result of positive or negative reinforcement. Elliott uses the “wanting and liking theory” to explain this. In a basic, non-technical explanation, the idea is that when you start using a drug or engage in a behaviour, a part of the brain is activated, which is the opioid system and represents the wanting part of the theory. It has a relaxing effect on our body and is responsible for endorphin rushes. The pleasure circuit is also activated, which involves dopamine, and this reinforces our behaviour to continue to use it, that is, the wanting part of the theory. Regardless of the drug or addictive behaviour, they are all in common in that they activate the dopamine system.

More relatable to the average person’s experience is the ideas of negative reinforcement. “With addictions, especially to drugs, you become tolerant and need more, and when you stop and try to break the addiction, we experience withdrawal symptoms. They are negative and not pleasurable, so people use other drugs or addictive behaviour to take away those negative feelings,” says Elliott. It is basically just replacing one bad thing with another. It can also be using drugs or behaviours to take away the pain of the past, or anxiety and depression.

Rae-anna Haugan, who works at a homeless shelter in inner-city Edmonton, sees this behaviour in many of the shelter’s occupants. “Most of the women that stay here have experienced some type of trauma or abuse and major loss, and resort to self-medicating,” Haugan says. Many of the women have trauma stemming from intergenerational issues with Indian Residential Schools.

“If somebody is in pain, they want to avoid that. What stops people from recovering from the addiction is whatever need the addiction is filling. Without getting the support for that emotional pain, there will always be a need for something to distract them from that,” says Haugan.

Another part that keeps the women Haugan works with and people with addictive behaviour addicted is the shame they may feel in what they are doing. Addiction has such a strong negative connotation that a lot of effort is needed to show someone that they do not have to be ashamed of what they do and where they are in their journey. That is the kind of help that Haugan and her co-workers provide at the shelter. They try to provide a type of freedom and grace to the women, to show them that when they are ready to move forward in their recovery, the staff will be there to support them without any judgement.

Haugan is quick to point out that there is no rule that says what you can and cannot be addicted to. One of her heroes in the field, Dr. Gabor Mate, often uses as an example the fact that he has an addiction to classical music. “This may not be seen as harmful, but its effect on the brain is similar to any addiction,” Haugan says. “By comparing our habits to determine which is good or bad we further stigmatize and shame those who need help. Those of us, for example, that may not smoke crack, but need a cup of coffee to start the day, have more in common with each other than we may realize.” This kind of message can go a long way in curtailing the negative preconception of addiction and, eventually, help people that are dealing with addictive behaviour.

Dr. Chris Alksnis, a psychology professor at Laurier Brantford, sometimes teaches a class regarding the reward centres linked to certain drugs, and the link between substance abuse and the overarching psychological issues. She uses marijuana as an example. “In the past, it was thought of as just a gateway drug, but now there does seem to be the case that evidence suggests it is not a great recreational drug for people of that age range, particularly if you have any kind of family history with psychological issues,” Alksnis says. She also mentions that the brain is most vulnerable during the university years.

“In a course like that where I’m talking to people of a certain age that are vulnerable to a specific drug, I feel it’s my responsibility to say that ‘hey this might not be the right one for you to take,’” says Alksnis.